- No products in the cart.

Body Unbeautiful: The Rise Of The Gothic Body In Contemporary African Art

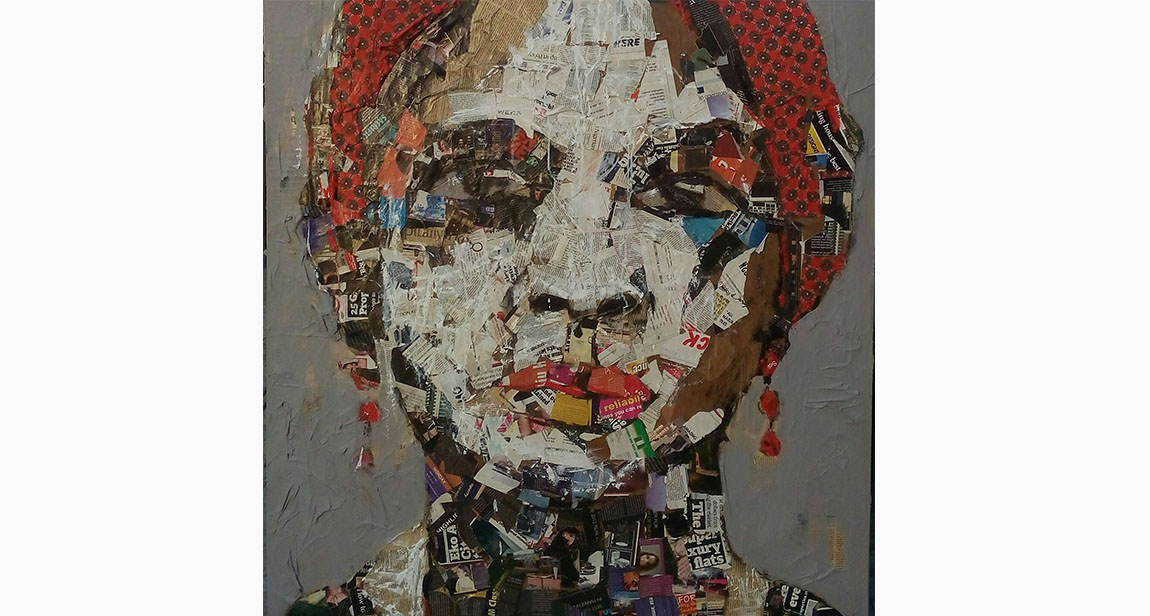

Abnormal, excessive, monstrous, tortured and admixed: Gothic bodies have made an increasingly frequent appearance in contemporary African art. This rising trend in the artistic representation of the body is somewhat at odds with more established traditions in the art of the region, in which the human body, particularly the female body, is depicted as an object of considerable beauty and splendor to which is to be admired by the onlooker. Indeed, as Richard J. Powell observes that African artists, more often than not, portray the human subject as both a statue–like artifact and object of sexual desire, contending that ‘since the 1960’s, depictions of the female body by African artists have ‘fused together traditional “feminine” qualities with the themes of omnipotence and physical potentiality’ (1). This description is a world away from the ways in which the body has previously been represented in the works of the Jane Alexander, Osahenye Kainebi and the artist collective MwangiHutter. This paper will examine works by these three artists in order to evaluate the incorporation of the Gothic style in contemporary art and the reasons behind their transformation of the human psyiogamy from a site of beauty and adoration into one of destruction “figured in the most violent, absolute, and often repulsive terms” (2). Defining the “Gothic Body”?

In order to understand how some of the work of these three artists engages with the notion of the “Gothic Body”, it is first necessary to get to grips and define exactly what is meant by that most problematic and slippery of terms, “Gothic”. The term “Gothic” is originally an architectural descriptor which has since been utilised to characterise particular strands of art, literature, film, culture, fashion and television. The Gothic architectural style flourished from the late 11th century until the early 14th century, with its most celebrated apogee being the Notre Dame cathedral in Paris, the Gothic style is characterised by the following features: a use pointed windows and arches; preference for the asymmetrical; structural orientation towards the sky (or other ethereal contexts); use of gargoyles and general excessive use of “dark” ornamentation. Overall, these features function to suggest “an over-abundance of imaginative frenzy” which is entirely at odds with demands for order and simplicity (3). The term “Gothic”, as a signifier of this particular style, is itself derived from the name of the Germanic tribe who sacked Rome in 410 AD, “the Goths”. Thus, the connection between the two terms lies in the symbolic opposition between, on one hand, ancient Rome – which represents ideas of civilisation, culture, law, and social and political coherency – and on the other the Goths – who embody, barbarism, decline, arbitrariness and an undesirable return to the “dark ages”. It is precisely these resonances of asymmetry, entropy and degeneracy that characterise a “Gothic body”, which, in other words, is the loss of a cohesive and unwavering bodily identity, and the materialisation of a disorganised, abominable and fluctuating identity in its place. The effect of the process of bodily transfiguration is the evocation of particular anxieties and terrors. Thus, as Catherine Spooner argues, a Gothic body”s capacity to disturb ”derives from [its] presentation of the body as lacking in wholeness and integrity, as a surface which can be modified or transformed” (4). It is arguable that following both colonisation and subsequent decolonisation, contact with the western world has been a highly formative experience, for African art in the twentieth century. Indeed, as Susan Vogel contends, “African artists select foreign ingredients from the array of choices [presented to them], and insert them into a preexisting matrix in meaningful ways” (5). This, I would argue, is precisely what has transpired with the interpolation of the Gothic body (which is essentially an Anglo–European tradition) into the contemporary African art scene, thus allowing artists such as Alexander, Kainebi and MwangiHutter: to incorporate Gothic bodies into their work with various employments and effects.

In order to understand how some of the work of these three artists engages with the notion of the “Gothic Body”, it is first necessary to get to grips and define exactly what is meant by that most problematic and slippery of terms, “Gothic”. The term “Gothic” is originally an architectural descriptor which has since been utilised to characterise particular strands of art, literature, film, culture, fashion and television. The Gothic architectural style flourished from the late 11th century until the early 14th century, with its most celebrated apogee being the Notre Dame cathedral in Paris, the Gothic style is characterised by the following features: a use pointed windows and arches; preference for the asymmetrical; structural orientation towards the sky (or other ethereal contexts); use of gargoyles and general excessive use of “dark” ornamentation. Overall, these features function to suggest “an over-abundance of imaginative frenzy” which is entirely at odds with demands for order and simplicity (3). The term “Gothic”, as a signifier of this particular style, is itself derived from the name of the Germanic tribe who sacked Rome in 410 AD, “the Goths”. Thus, the connection between the two terms lies in the symbolic opposition between, on one hand, ancient Rome – which represents ideas of civilisation, culture, law, and social and political coherency – and on the other the Goths – who embody, barbarism, decline, arbitrariness and an undesirable return to the “dark ages”. It is precisely these resonances of asymmetry, entropy and degeneracy that characterise a “Gothic body”, which, in other words, is the loss of a cohesive and unwavering bodily identity, and the materialisation of a disorganised, abominable and fluctuating identity in its place. The effect of the process of bodily transfiguration is the evocation of particular anxieties and terrors. Thus, as Catherine Spooner argues, a Gothic body”s capacity to disturb ”derives from [its] presentation of the body as lacking in wholeness and integrity, as a surface which can be modified or transformed” (4). It is arguable that following both colonisation and subsequent decolonisation, contact with the western world has been a highly formative experience, for African art in the twentieth century. Indeed, as Susan Vogel contends, “African artists select foreign ingredients from the array of choices [presented to them], and insert them into a preexisting matrix in meaningful ways” (5). This, I would argue, is precisely what has transpired with the interpolation of the Gothic body (which is essentially an Anglo–European tradition) into the contemporary African art scene, thus allowing artists such as Alexander, Kainebi and MwangiHutter: to incorporate Gothic bodies into their work with various employments and effects.